Understanding Disaster Recovery in PostgreSQL

System outages, hardware failures, or accidental data loss can strike without warning. The strength of your disaster recovery setup determines whether operations resume smoothly or grind to a halt. PostgreSQL comes equipped with robust, built-in features for achieving reliable recovery.

This article takes a close look at how these components work together behind the scenes to protect data integrity, enable consistent recovery, and ensure your database can bounce back from any failure scenario.

What is Disaster Recovery?

Disaster Recovery (DR) refers to the set of practices and strategies designed to back up and restore a database in the event of a disaster. In this context, a disaster is any incident that renders the entire database environment unusable, such as:

- Cloud region outage – e.g., AWS us-east-1 fails, taking half the internet down

- Physical disasters – Fire, flood, earthquake, or even a backhoe cutting a fiber line

- Catastrophic human error – e.g., a faulty migration that corrupts a critical table

- Major security incident – Requiring rebuilding from a known-good backup

- Extended power failure – Prolonged downtime affecting availability

- Hardware failure – Disk, memory, or server crashes

- Software failure – Bugs, crashes, or process corruption

- Cyber attacks – Ransomware, data breaches, or malicious tampering

- ...and anything else you can imagine!

The goal of DR is to ensure the system can be quickly restored to a functional state following an unexpected event.

Pillars of Business Continuity: RTO and RPO

Before designing a disaster recovery strategy, we must understand the two metrics that define it:

- Recovery Point Objective (RPO): The maximum amount of data loss you can tolerate when a failure occurs, measured in time. It answers the question: "How far back in time will we be when we recover?" If you can only tolerate 5 minutes of data loss, your RPO is 5 minutes. RPO is primarily a disaster recovery metric, directly tied to your backup and WAL archiving strategy.

- Recovery Time Objective (RTO): The maximum acceptable time to restore services after a failure. It answers: "How long can the application be down?" If you need to be back online within 30 minutes, your RTO is 30 minutes. RTO is primarily a high availability metric, often addressed with replication and failover mechanisms.

These two metrics often conflict, and the goal is to bring both RTO and RPO as close to zero as possible. A low RPO requires frequent backups and robust WAL archiving, which can be costly. A low RTO requires on-demand computing resources and automation, which also adds expense. The essence of DR planning is finding a balance between these opposing factors through risk management and cost-benefit analysis.

The Evolution of PostgreSQL

One of the most impressive aspects of Postgres is its out-of-the-box flexibility and resilience. As early as 2001, Postgres made a significant leap with the introduction of crash recovery via Write-Ahead Logging (WAL), a milestone for data durability. In 2005, the introduction of continuous backup and point-in-time recovery features enhanced Postgres's capabilities through online physical backups and WAL archiving, enabling effective disaster recovery.

Over the next decade, Postgres evolved its continuous backup framework into the sophisticated replication system we know today, built to meet the high availability needs of modern organizations. Before diving into Postgres backup and recovery infrastructure, let's cover some fundamental concepts.

What is a Backup?

A backup is a consistent copy of data that can be used to restore a database. Without backups, there is no real disaster recovery plan. There are two main types:

- Logical Backups

- Physical Backups

Logical Backups

A logical backup captures the database contents by exporting them into an SQL script or other portable format. It is a set of commands that can recreate the database's structure (including tables, schemas, constraints) and re-insert all the data. Common tools include:

pg_dump– Creates a backup of a single database.pg_dumpall– Captures the entire cluster, including all databases, roles, and global objects.

Physical Backups

A physical backup is a low-level copy of the database's actual files at the storage layer. They capture the exact state of the database by directly copying the underlying data files. Common tools are:

pg_basebackup– The standard tool for online physical backups.pgBackRestorBarman– These are external tools that add automation and better management for large-scale environments.

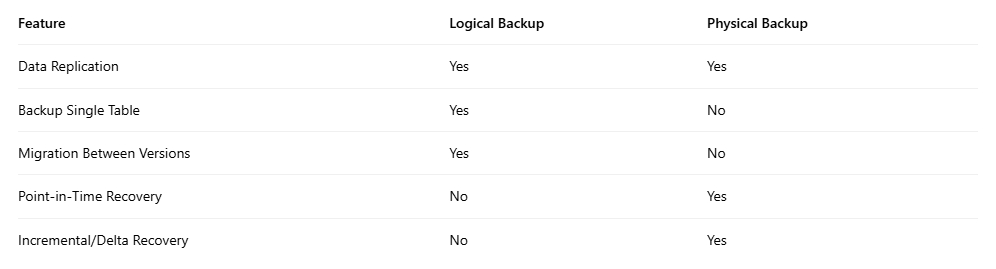

Logical vs. Physical Backups: Pros and Cons

Here is a quick comparison of the differences in functionality and use cases:

In short, logical backups are flexible, portable, and suitable for migration, while physical backups are faster, support point-in-time recovery, and scale more efficiently for large production environments.

Write-Ahead Logging (WAL)

To understand PostgreSQL's recovery mechanisms, we must understand WAL. It is the most critical component for persistent storage.

In the foundational diagram below, there are four main components:

- Shared Buffers

- PG Data

pg_wal- Postgres Backend

Let's understand these first. Postgres stores data in a directory called PGDATA, with each page being 8 KB in size. The transaction log is stored in Write-Ahead Log (WAL) files within the pg_waldirectory. The shared buffers act as an in-memory cache for performance, and each client connection is handled by a dedicated process known as a Postgres backend.

PostgreSQL's golden rule is that any modification to a data page must be recorded in the Write-Ahead Log (WAL) before the updated ("dirty") page can be written back to the data file.

When a backend requests a page from the disk, the page is first loaded into the shared buffers before being returned to the backend. If the backend modifies the page, the change is first recorded in the Write-Ahead Log (WAL), not directly in the data file. This information is written to a WAL segment, hence the mechanism is called Write-Ahead Logging, or simply WAL.

[Image description: A diagram showing data flow: A Postgres Backend reads/writes to Shared Buffers. The WAL Writer writes records to the pg_wal directory. The Background Writer writes dirty pages from Shared Buffers to the PG Data files.]

(Source: https://stormatics.tech/blogs/understanding-disaster-recovery-in-postgresql)

The Write-Ahead Log (WAL) is a binary representation of every precise change made to the data files. Each WAL record contains these key details:

- Transaction ID – Identifies which transaction made the change.

- Page Information – Specifies which database page was modified.

- Redo Information – Describes how to reapply the change.

- Undo Information – Describes how to undo the change (for rollbacks).

- CRC Checksum – Detects corruption and ensures data integrity.

Each WAL record is first written to a small, high-speed memory area called the WAL buffer. When a transaction commits, PostgreSQL guarantees that the relevant WAL records are physically written to a file in the pg_waldirectory. This marks the transaction's durability; once the WAL is safely on disk, the transaction is considered permanent. Even a sudden power loss cannot erase it.

After the WAL is written, PostgreSQL can delay writing the actual modified ("dirty") data pages back to disk until a more convenient time. PostgreSQL coordinates this process through checkpoints. A checkpoint is a point in time when all dirty data pages are flushed to disk, ensuring the data files are consistent with the WAL up to that point.

Once all changes recorded in a WAL file have been applied to the data files, that WAL segment is no longer needed for crash recovery. Instead of deleting it, PostgreSQL recycles its space for future WAL records. For disaster recovery, we leverage this mechanism by configuring WAL archiving. We don't let PostgreSQL recycle old WAL files; instead, we archive each WAL file to a separate, secure location.

So, in short, to ensure reliable disaster recovery, it is crucial to protect Postgres database backups and WAL archives. Together, they form the foundation for Point-in-Time Recovery (PITR) and act as the cornerstone for Postgres replication.

Continuous Backup and WAL Archiving

We need continuous backups and WAL archiving to ensure reliable disaster recovery. Now let's look closely at how these mechanisms work in practice.

While the Postgres server is running, it continuously generates WAL files, recording every change to the database. These WAL files are periodically archived to a separate storage location, typically an object store like Amazon S3 or Google Cloud Storage.

Simultaneously, the data files in the PGDATA directory need to be physically copied; this is known as a base backup. Postgres provides an API to take these backups while the database remains online, known as hot physical backups.

The process is straightforward:

- Invoke the Postgres API to start a backup (

pg_backup_start). - Begin copying all files from PGDATA. Depending on database size, this step could take minutes or even hours.

- During this time, ongoing changes continue to be recorded in the WAL, ensuring nothing is lost. These WAL records are also continuously sent to the WAL archive.

An important point to note: during an online backup, since the database is still active, data files in PGDATA might change while being copied. At first glance, this looks like data corruption because the copied files are not perfectly synchronized with the database's current state. However, this is not actually a problem.

Postgres is designed to handle this gracefully through Write-Ahead Logging (WAL). Every change made to the database is first recorded in the WAL, which is being continuously archived. Therefore, even if the base backup contains some files mid-update, all subsequent or missing changes are safely recorded in the WAL archive.

Upon recovery, Postgres first restores the base backup and then replays the WAL files in sequence. This replay process reapplies every recorded change that happened after the backup started, bringing the database to a fully consistent state, as if the interruption never occurred.

[Image description: A timeline diagram showing Base Backup creation, followed by a continuous stream of WAL files (WAL 1, 2, 3...). Recovery involves restoring the Base Backup and then replaying the sequence of WAL files.]

(Source: https://stormatics.tech/blogs/understanding-disaster-recovery-in-postgresql)

Finally, the backup process signals the end of the copy operation via the Postgres API (pg_backup_stop) and waits for the final WAL file to be archived. This ensures all transactions up to that point are captured, completing a consistent and recoverable backup. For a backup to be recoverable, we must have all WAL files from the start to the finish of the backup.

Therefore, if the production database is running smoothly, it continuously generates WAL files as transactions occur. Over time, these files are recycled and archived sequentially. Our responsibility is simply to schedule regular base backups and maintain continuous WAL archiving. Together, these measures ensure the database can be restored completely and accurately to any specific point in time.

Point-in-Time Recovery (PITR)

Point-in-Time Recovery (PITR) is one of the most powerful features, enabling us to restore your database to a specific moment in the past.

As long as we have a base backup directory and a continuous sequence of WAL files safely stored in an archive, PostgreSQL can reconstruct the database state at any specific point in time, from the moment the earliest base backup ended to the latest committed transaction captured in the most recent WAL segment.

Suppose a developer accidentally runs DROP TABLE customers;at 2:05 PM on October 4, 2024. With PITR, we can "rewind" to just before that command was executed.

The Recovery Process:

- Restore: First, configure a new PostgreSQL instance and restore the latest base backup to it.

- Configure Recovery: Next, create a

recovery.signalfile and update thepostgresql.conffile to point to the actual WAL archive. Then define a recovery target, for example: recovery_target_time = '2024-10-04 14:04:00'- (One minute before the accidental drop).

- Recover: When PostgreSQL is started, it enters recovery mode and begins fetching WAL files from the archive. It replays every committed transaction recorded in the logs in sequence until it reaches the specified recovery target.

- Promote: Once recovery reaches the set target time, PostgreSQL pauses. We then promote the server, turning it into a fully operational primary database, restored to the exact state just before the incident, with the customer table safe and sound.

By combining base backups with continuous WAL archiving, PostgreSQL empowers us to restore data to any precise moment. We just need to set up three things:

- Regular base backups

- Configuration for continuous WAL archiving

- Distribution of backups and WAL files across multiple locations to enhance global RPO and RTO targets

High Availability vs. Disaster Recovery

High Availability (HA) and Disaster Recovery (DR) often go hand-in-hand but serve different purposes.

- High Availability (HA) means having multiple active copies (nodes) of the production database running synchronously. If one node fails, slows down, or is overloaded, another node takes over immediately, keeping the system available with minimal disruption.

- Disaster Recovery (DR), on the other hand, kicks in when the entire environment fails (e.g., a regional outage or major data loss). It relies on backups and archived WAL files to fully restore the database to a specific point in time, often in a different region or data center.

Imagine a primary PostgreSQL cluster running in the AWS us-east-1 region. If a single node fails, HA mechanisms promote a secondary node within seconds, ensuring service continuity. But if the entire region goes offline, DR takes over: the database is restored from backups and WAL archives in the us-west-2 region, bringing it back to the exact state before the failure. Once the primary region is restored, it can be resynchronized.

HA and DR together form a two-tier defense:

- HA keeps the system running during local failures.

- DR ensures recovery after large-scale disasters.

Conclusion

PostgreSQL provides a solid foundation for enterprise-grade disaster recovery. With Write-Ahead Logging, physical base backups, and point-in-time recovery, it can meet stringent RPO and RTO objectives.

But true resilience doesn't come from backups alone—it requires a well-architected, automated, and regularly tested disaster recovery plan combined with periodic drills. Coupled with a robust high availability setup, this ensures data safety and uninterrupted service, even when failures occur.

%20(2048%20x%201000%20%E5%83%8F%E7%B4%A0)%20(3).png)

%20(2048%20x%201000%20%E5%83%8F%E7%B4%A0)%20(2).png)